|

Why mention D.A.R.E., the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E) 1 program that was rolled out in 1983 as the model program to prevent children and youth from using drugs in a blog for NCH2? Because as researchers we are often asked why there is a need for more research on the health benefits of engaging with nature when it seems so clear that nature is good for us. Research is needed because there are many unanswered questions about who benefits from engaging with nature, and why, what “nature” means to different people, and what the best practices are for helping diverse people gain the beneficial effects of nature. These questions are at the center of a recent article by Phi-Yen Ngyuen, Thomas Astell-Burt, Hania Rahimi-Ardabili, and Xiaoqi Feng in The Lancet Planetary Health.2

In 1983 political leaders thought D.A.R.E. was wonderful, until they didn't. Retrospective analysis showed that D.A.R.E. in its original form, did not reduce drug use or save lives, and may have increased drug use. The D.A.R.E. program has since been reconfigured and the new program has very different goals, however the journey of D.A.R.E from a $10 million/year drug prevention program to a program that “teach[s] students good decision making [sic] skills to help them lead safe and healthy lives” is illustrative of the importance of rigorous program evaluation and research. 1 Ngyuen et al. (2023) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of peer-reviewed papers that describe original research or evaluation of nature prescription programs. For their paper, the authors describe a nature prescription as “typically involve[ing] a health professional (e.g., a general practitioner) or social professional (e.g., a counselor or welfare officer) recommending a patient to spend a fixed amount of time a week in a natural setting, such as a park.” This definition was used to identify publications that contained information about programs that were either described by the original authors as a nature prescription program or fit the description of a nature prescription program regardless of whether the original authors used the specific term “nature prescription.” Systematic reviews of randomized control trials are the pinnacle of the hierarchy of evidence recognized by biomedical researchers.3 The reason for this prominence is that systematic reviews use rigorous methodologies to examine the existing literature to draw conclusions about the weight of evidence from many studies. This is much stronger than relying on what any single study shows. Meta-analyses add an additional level of strength by using statistical methods to compare the results of the reviewed articles to provide an estimate of the overall size of the effect of the various interventions. Effect size tells us how large the response is, and whether the response is likely to be clinically relevant, not just whether it is statistically significant. Conducting a meta-analysis requires that the methods used by different researchers be sufficiently well described and sufficiently compatible that they can be compared directly. Systematic reviews also examine the extent to which the body of literature may be influenced by bias, either intentionally or unintentionally. Nguyen et al. initially found 4,309 records of peer-reviewed publications that might fit the objectives of their review. They included randomized and non-randomized controlled trials. However, further winnowing using approved procedures for systematic reviews resulted in only 92 papers that were appropriate for the systematic review and 28 that could be included in a meta-analysis. Papers were excluded from the review if they described interventions such as building new green spaces, outdoor gyms, programs requiring “high levels of safety and skilled organizers (e.g., wilderness adventures)”, etc. Papers were included if the intervention “…took place in a park or was organized by a health or social institution for patients or clients and used nature-based therapy to improve health outcomes…” The analysis examined what age groups were studied, which pre-existing conditions patients had, what types of settings were used, the types of activities recommended, and the health outcomes measured (“physical, psychological, or cognitive health, and behavioral outcome”) . Their analysis showed that nature prescriptions do lead to better outcomes than the control (usual or standard care) for systolic and diastolic blood pressure, depression and anxiety, and greater increases in daily step count. Nature prescriptions, however, did not lead to an increase in medium to vigorous physical activity, the type of physical activity needed to provide many health benefits. Additionally, while many individual papers reported improvements in many other physical health measures (e.g., improved balance, reduced pain) there was insufficient evidence to draw generalizable conclusions. Thus, those of us who advocate for nature prescriptions need to be cautious when we make claims about specific health benefits. Nguyen et al. also report that most of the studies they examined had a high risk of bias. They found multiple sources of bias, the most obvious being that it is nearly impossible to “blind” either the researchers or the participants to the intervention they are receiving. People know where they are walking and spending time. Another source of bias is the small sample sizes used in individual studies and high numbers of people who drop out of the studies before they are completed. We must ask ourselves these high dropout rates are telling us about how nature prescriptions are implemented. However, the strength of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, is that if multiple small studies show the same trends, we are probably onto something. Importantly for those interested in health equity, the literature is heavily biased toward people from a few populations. Most studies of nature prescriptions are done in high-income countries, most interventions took place in South Korea, the U.S.A., or Japan. Studies are also limited in their recruitment of individuals from socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, only 11% of studies recruited participants from these groups. Thus, we should question how generalizable the results are among cultures. What does this mean for the use of nature prescriptions? Nguyen et al. have done researchers and practitioners of nature prescriptions a huge service by pointing out where we have strong evidence for the benefits of nature prescriptions, and by showing us where there are weaknesses in the evidence. If we are to build policy and programs using nature prescriptions, it is important for us to know whether those programs and policies are created in a way that will benefit the people for whom they are intended, whether they are sufficiently feasible and attractive that people will stick with them. This is why NCH2 was created around a culture of research and evaluation. NCH2 seeks to share both what we know and don’t know about the health benefits of engaging with nature, and to encourage a community that contributes to building that evidence base. References:

0 Comments

When I’m feeling lonely, I have two lines of defense. My first line of defense: I set up social plans. In the meantime, I enact my second line of defense: I get outside, even if the walk I take is solo. These two responses kick in for me as natural solutions. Feeling lonely? Make some plans and get out of the house! We are used to attributing loneliness -- a felt deprivation of connection, companionship, and camaraderie -- to person-level causes, like a move or a break-up, and person-level solutions, like initiating connection with a local hobby group. Xiaoqi Feng and Thomas Astell-Burt, researchers at the Population Wellbeing and Environment Research Lab at the University of Wollongong in New South Wales, Australia, say that our conception of loneliness as a person-level issue prevents us from seeing the whole picture. Their December 2022 ‘comment’ (expert opinion) in The Lancet: Planetary Health breaks down the factors creating what they call ‘lonelygenic environments.’ First, the authors establish that aside from its association with anxiety and depression, loneliness has a stigma of its own. Speaking for myself, I find it embarrassing to be lonely and judge myself for not making more plans or sufficiently investing in friendships. Feng and Astell-Burt say loneliness is rational because our environment generates feelings of loneliness. “It is the shortsighted, inadvertant [sic], reckless, and negligent decisions made across society, fostering stigma and structural discrimination (racism, sexism, ableism, classism), that generate social and built environments that make many people with these characteristics feel perpetually isolated and unsafe,” write the authors. Just as the discrimination embodied in our built and social environments impacts our health, it also impacts our loneliness. Say that you are a person using a wheelchair who finds that to enter a local park, you need to ascend a staircase. Does this make you feel as though your needs were considered in designing this public space? Do you feel that this space welcomes you? We take the cues our environments give us. In addition to placing value on our social identities, Feng and Astell-Burt say, our built environment gives us cues indicating the “near universal prioritization of cars over people across societies”. In a car-centric society, our interactions are chosen based on our personal safety. A driver encounters another driver as an unpredictable potential threat about whom they must be constantly vigilant. The pedestrian-driver relationship is similarly fraught: two humans interacting becomes an interaction of a human on foot and a human operating a hulking, dangerous machine. Our commutes are defined by interactions that make us feel threatened and embittered. The impact of our car-centric society also extends to the built structures we have prioritized over recent decades. What does the construction of an interstate over or through your neighborhood, or the house you used to own being seized as a part of ‘urban renewal’ under ‘eminent domain’ and replaced with a university parking lot, tell you about how much your way of life is valued and respected? “Electric vehicles will not change” the prioritization of cars over people, the co-authors state, because although they reduce carbon emissions, they contribute to ‘lonelygenic environments’ just the same as gas-powered cars. A turn toward investment in public transportation and compact cities is part of the answer. Although travelling in proximity to others acts as one buffer to loneliness, public transportation and compact cities’ most crucial buffer is the access they unlock to third places, such as parks, libraries, or cafes, outside of home or work which, Feng and Astell-Burt say, create space for complex social interactions which help to combat loneliness. This access is especially important to older adults, others experiencing mobility issues, and those without the ability to drive or access a car. The authors also cite tree canopy as a crucial third place, the loss of which “is depriving people of the settings where nourishing connections and community spirit can be fostered,” "disproportionately in lower-income communities.” Feng and Astell-Burt's call to action is to “establish a foundation of evidence that measures lonelygenic environments, which could vary from place to place,” and integrate it into current strategies to reduce loneliness to make them more effective. This leaves plenty of flexibility to adapt measures to community needs: what characteristics make up the ‘lonelygenic environment’, as well as the size, scope and boundaries that define these environments, are left to the researcher. But Feng and Astell-Burt make a powerful case for a new conception of loneliness that breaks down its causes from all angles, helping researchers like us identify new targets to reduce it. Abby Kisicki is NCH2’s Research Editor. She serves as the Research Coordinator for the Horton Research Group (HRG) at Northwestern University. Led by Dr. Terry Horton, HRG is an interdisciplinary research group at Northwestern which studies the health benefits of and access to green and blue spaces.

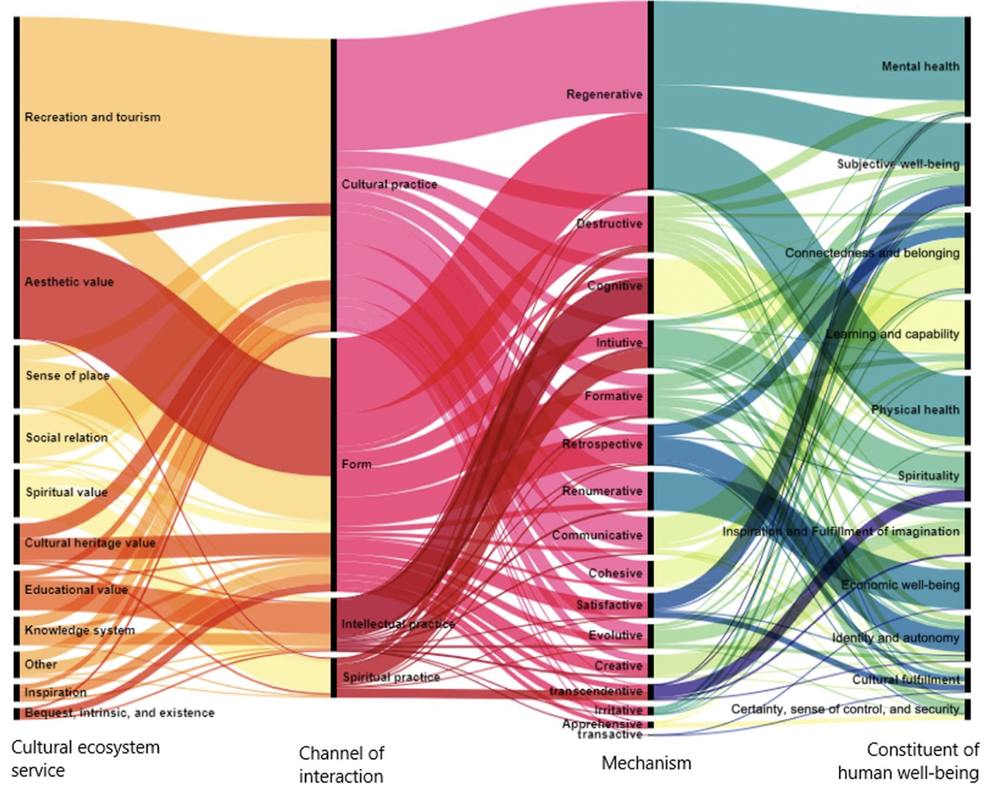

Picture this: you’re lying flat on your back on soft, cool, grass under a tree. The sun soaks into your skin, but the shade from the tree shields your eyes as you stare up into the clouds. What is this feeling? Could be peace, could be joy. How do moments like these shape the rest of your day? The rest of your life? These are benefits of nature, the intangible effects on our bodies and minds that keep us coming back to green spaces. The social sciences and humanities help us understand these benefits. In a newly published systematic review paper written by Lam Thi Mai Huynh and an international team of colleagues, these intangible emotional, cultural, and spiritual benefits of nature are quantified in a new way that will have lasting effects on communities and individuals– from policy or funding changes, to increased social engagement within neighborhoods. And while it may not seem important to research enjoying nature, understanding how and why we feel so good in nature is in fact important for our health, our connection to the earth, and how to help others build those connections. The term “ecosystem services” describes the products and patterns of nature that benefit humans, like how forests can control carbon dioxide levels in the air, and how soil allows crops to grow. But we have a reciprocal relationship with nature that goes beyond taking its “material” resources, or utilizing its physical processes like forests’ air regulation. Research can help us understand the intrinsic connection we have with nature, and can help us take and give back to the earth in meaningful, “non-material” ways. The non-material benefits humans get from nature are called cultural ecosystem services (CES). CES can include recreation, spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, social relations, and aesthetic values. This paper is groundbreaking, and a new way of thinking about how we use and conduct scientific research. The review paper examines the effects of CES on our spiritual, mental, physical and social health. In their systematic review of 301 studies conducted throughout the world, the majority of which (81.8%) focus studies that examined interventions conducted on a local scale, Huynh et al. identified 227 individual pathways by which CES affect overall human wellbeing. These pathways indicate how cultural, intellectual, and spiritual interactions, or physical and tangible interactions with nature result in various effects on our well being. Graphic illustrating these pathways (Figure 2 from Huynh et al. 2022): In this graphic (an alluvial diagram), thicker line width indicates a high number of studies that link certain elements. For instance, the Cultural ecosystem service (left most column)‘Recreation and Tourism’ and ‘Aesthetic value’make up a large bulk of published studies , and these typically go through the Channel of interaction of ‘Cultural Practice’ and ‘Form’. The ‘Regenerative’ Mechanism is a common pathway linking these Channels of Interaction to the Constituents of human well-being of both ‘Physical health’ and ‘Mental health’ along with subjective accounts of general well-being (‘Subjective well-being’). But what does all this mean?

This paper, complex and thought-provoking, confirms that we’re on the right track with our focus on ensuring and increasing access to nature, and to encouraging a “cultural” immersion in nature–how our heritage and families spent time outside. Through these CES that we engage in nature spaces, we can improve our mental, physical and spiritual health. Being able to quantify such abstract ideas means that we can be certain of the value of our attachment to nature. Being able to identify the different pathways that connect CESs to well-being can help identify which elements we should consider when designing programming to enhance people’s engagement with nature. |

AuthorsTerry Horton, Ph.D. Archives |

DISCLAIMER: All information, content, and material on this website is for informational purposes only. This information should not replace a medical consultation or treatment plan given by a qualified healthcare provider.

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed