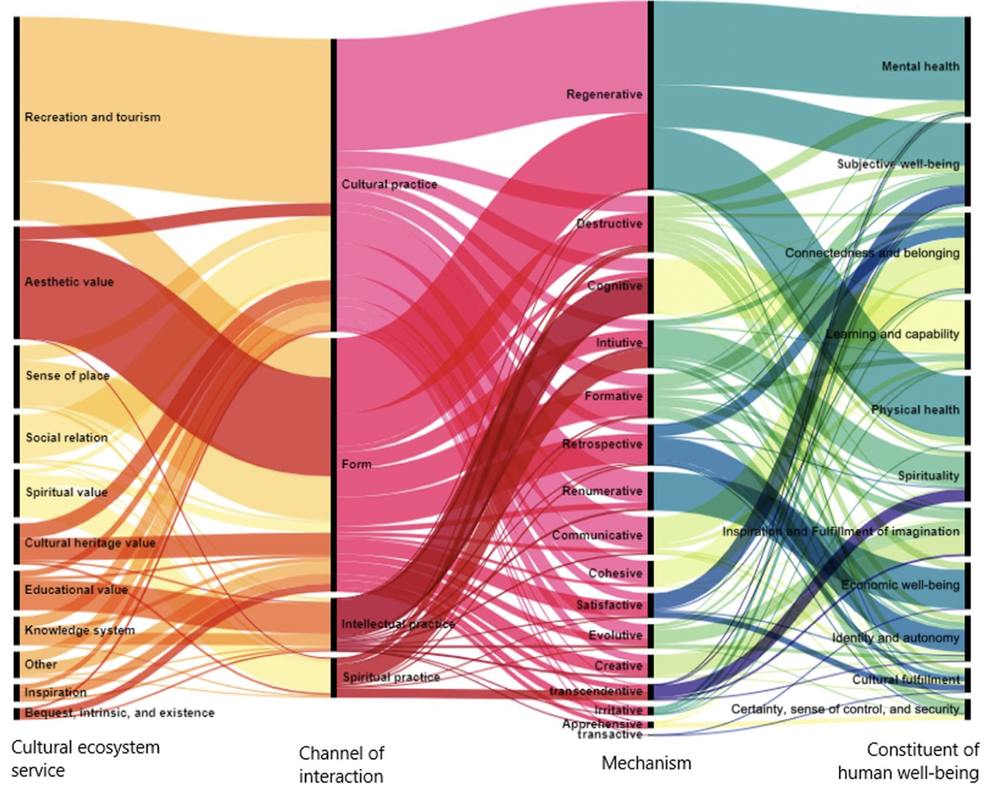

Picture this: you’re lying flat on your back on soft, cool, grass under a tree. The sun soaks into your skin, but the shade from the tree shields your eyes as you stare up into the clouds. What is this feeling? Could be peace, could be joy. How do moments like these shape the rest of your day? The rest of your life? These are benefits of nature, the intangible effects on our bodies and minds that keep us coming back to green spaces. The social sciences and humanities help us understand these benefits. In a newly published systematic review paper written by Lam Thi Mai Huynh and an international team of colleagues, these intangible emotional, cultural, and spiritual benefits of nature are quantified in a new way that will have lasting effects on communities and individuals– from policy or funding changes, to increased social engagement within neighborhoods. And while it may not seem important to research enjoying nature, understanding how and why we feel so good in nature is in fact important for our health, our connection to the earth, and how to help others build those connections. The term “ecosystem services” describes the products and patterns of nature that benefit humans, like how forests can control carbon dioxide levels in the air, and how soil allows crops to grow. But we have a reciprocal relationship with nature that goes beyond taking its “material” resources, or utilizing its physical processes like forests’ air regulation. Research can help us understand the intrinsic connection we have with nature, and can help us take and give back to the earth in meaningful, “non-material” ways. The non-material benefits humans get from nature are called cultural ecosystem services (CES). CES can include recreation, spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, social relations, and aesthetic values. This paper is groundbreaking, and a new way of thinking about how we use and conduct scientific research. The review paper examines the effects of CES on our spiritual, mental, physical and social health. In their systematic review of 301 studies conducted throughout the world, the majority of which (81.8%) focus studies that examined interventions conducted on a local scale, Huynh et al. identified 227 individual pathways by which CES affect overall human wellbeing. These pathways indicate how cultural, intellectual, and spiritual interactions, or physical and tangible interactions with nature result in various effects on our well being. Graphic illustrating these pathways (Figure 2 from Huynh et al. 2022): In this graphic (an alluvial diagram), thicker line width indicates a high number of studies that link certain elements. For instance, the Cultural ecosystem service (left most column)‘Recreation and Tourism’ and ‘Aesthetic value’make up a large bulk of published studies , and these typically go through the Channel of interaction of ‘Cultural Practice’ and ‘Form’. The ‘Regenerative’ Mechanism is a common pathway linking these Channels of Interaction to the Constituents of human well-being of both ‘Physical health’ and ‘Mental health’ along with subjective accounts of general well-being (‘Subjective well-being’). But what does all this mean?

This paper, complex and thought-provoking, confirms that we’re on the right track with our focus on ensuring and increasing access to nature, and to encouraging a “cultural” immersion in nature–how our heritage and families spent time outside. Through these CES that we engage in nature spaces, we can improve our mental, physical and spiritual health. Being able to quantify such abstract ideas means that we can be certain of the value of our attachment to nature. Being able to identify the different pathways that connect CESs to well-being can help identify which elements we should consider when designing programming to enhance people’s engagement with nature.

1 Comment

|

AuthorsTerry Horton, Ph.D. Archives |

DISCLAIMER: All information, content, and material on this website is for informational purposes only. This information should not replace a medical consultation or treatment plan given by a qualified healthcare provider.

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed